We imagine a creative person as a messy genius, with paint splashed everywhere, dishevelled hair and wild emotions. But in reality, creative people are like two sides of a coin: willing to experience temporarily chaos, but only for a long term vision; messy, but also very organised. After all, a painter needs to ensure their brushes are readily available when they need them.

The misconception comes from the initial spark of creativity, which often is messy, unpredictable and chaotic. Musicians, painters and writers learn to navigate their way through the first foggy stage by using their taste, instincts and experience until they have something that resembles their initial idea. The initial stage is like being a gardener – planting the seeds, waiting for them to grow and then nurturing them; falling in love with process. The second stage is more like being an architect, using logic, structure and order, and falling in love with the outcome.

I have a friend who is an astrophysicist and I often wish I could do the things he can do. Recently I was talking to him about my writing and he said, “I have no idea how you do that”. And that was when I realised that being creative is not something everyone feels comfortable with. Some people are more comfortable with numbers and a definite, concrete outcome. The messy initial stages of creativity are unbearable for some people, as they haven’t developed their internal compass to navigate through it. If you sit down to write a song, there are no guarantees or tangible truths to guide you there.

However intangible, creativity is also something that can be practised. There is no need to wait for “inspiration”, you only need to sit down and start. See what comes out. It may be mediocre, but that’s okay – just learn from it and know that the next thing you create will be a little bit better. You need to write 100 bad songs before you write your first good song. Before writing this post, I felt stuck and didn’t know what to write, so-called “writer’s block”. After much procrastination, I realised I just needed to write down the first few words and the rest would eventually come.

Creativity takes time, reflection and patience, but it is easy to lose these virtues with so many distractions readily available to absorb our senses. So whatever you want to create, just make a start right now, even if it is just the first twenty words of your novel, the first three chords of your song, or the initial pencil sketch for your oil painting. Make a start. And then do the same tomorrow.

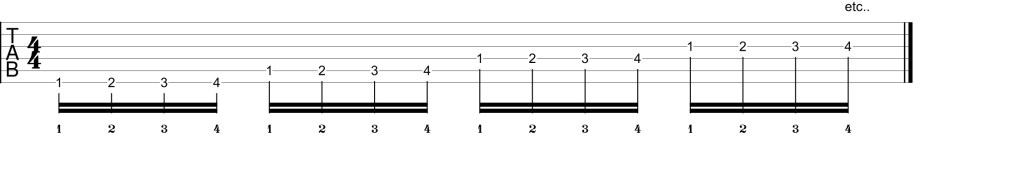

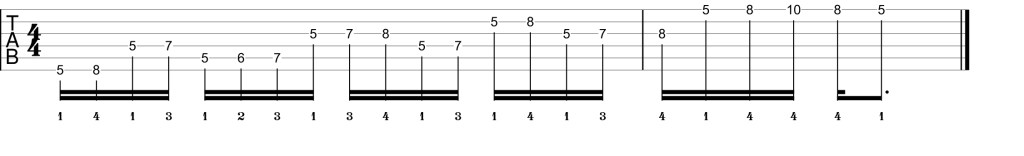

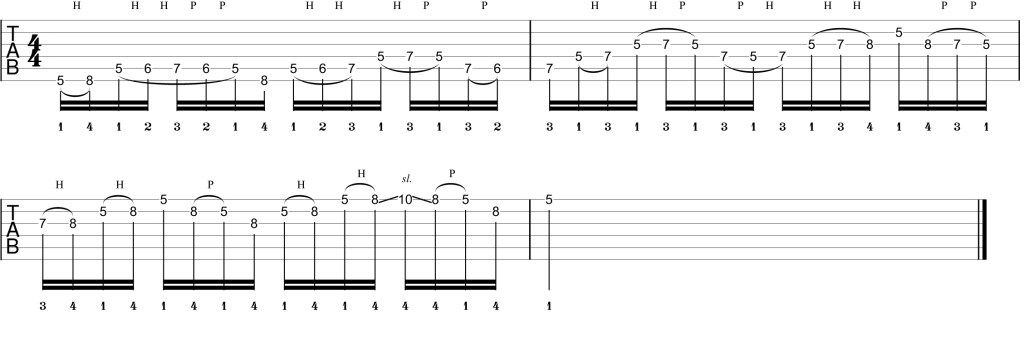

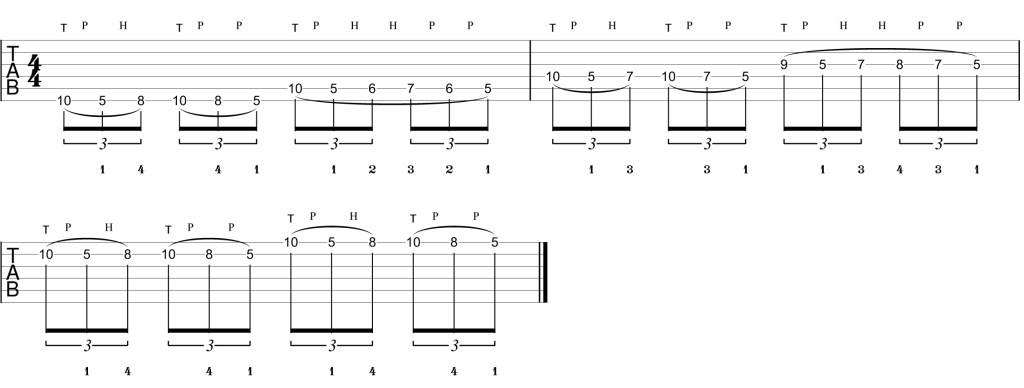

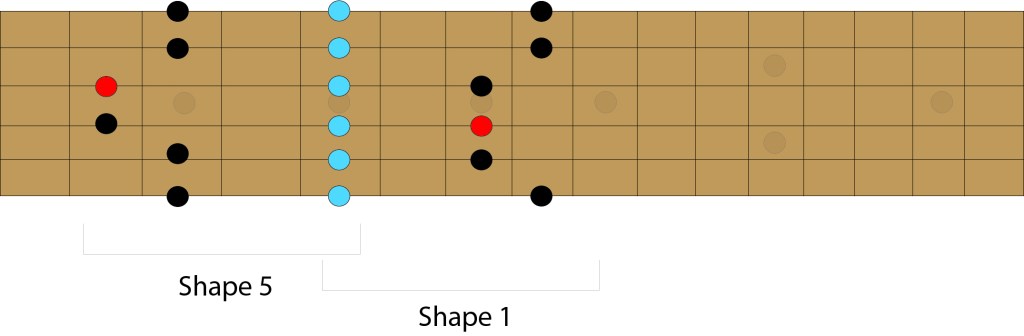

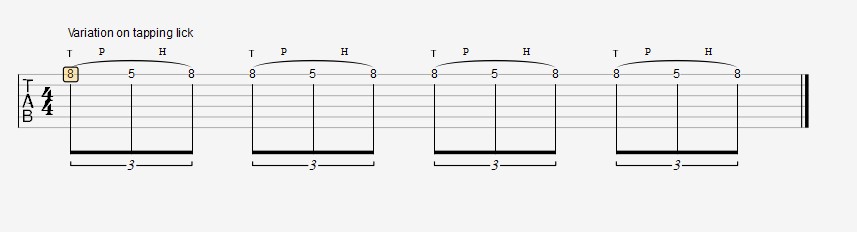

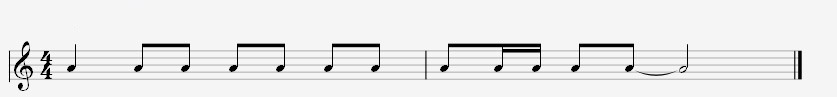

My latest book “Guitar Gymnasium” is available on Amazon: