Inertia and momentum are both spirals, one negative, the other positive. During my own periods of inertia I feel stuck yet unwilling to take any action to improve my circumstances.

But I’ve also experienced the upward spiral where I am taking action with focus, joy and a calm aggressive determination.

What I’ve noticed about both of these states is that they seem to spill over into other domains. When I’m taking consistent action writing or practising music, I find it easier making my bed in the morning or fixing that broken door hinge. Conversely, when I’m feeling stuck and refusing to improve my situation, I notice that I’m more reluctant to do chores around the house or exercise. It seems like “taking action” is a muscle which can rapidly atrophy within a day or so when not used.

I’ve read many great books on the science of motivation and many acknowledge that motivational “theory” is not enough. To actually take action we need incentive, accountability, a bit of fear, a bit of ego, a bit of confidence, a bit of insecurity, mixed with the possibility of public ridicule if we don’t succeed. Humans are such complex machines and yet in some ways we are also very simple: I may not want to go for a run, but if a lion was chasing me I would suddenly have an incentive to sprint for many miles.

Intellectually I realise that if I just start for two minutes, that would be enough to gain traction and slowly build momentum. But so often I get bogged down in theory, insecurity and the idea of “perfection” that I don’t get started.

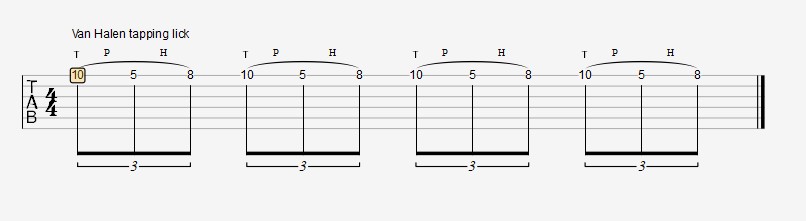

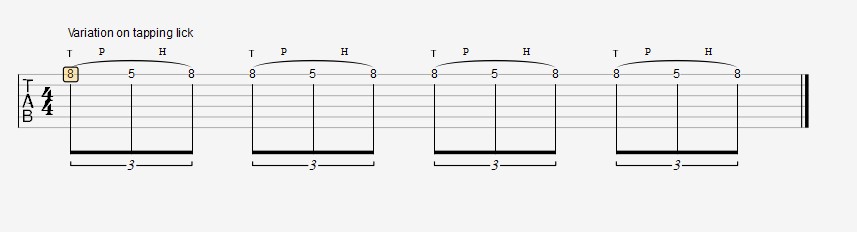

There is also the element of being overwhelmed by too many choices. When searching YouTube for a guitar tutorial, it is easy to flick through the endless stream of videos and never really make a start.

One way I counteract this is to create a schedule. I like to be organised and write out my goals for the year, breaking them down into quarters (i.e. January to March) and then every Friday I write out a schedule for the coming week, so I don’t need to think about what I need to do, I can just execute the task to move nearer to my goals.

Scheduling means I can live my week deliberately whilst scheduling time to watch television or go to the cinema without feeling guilty. It also lets me see where my time is being allocated, so if one of my goals is not scheduled in, I can try to adjust for that the following week or see why it won’t fit into my schedule.

Disclaimer: During the current covid-19 lockdown I haven’t been doing my weekly schedule and I have noticed a creeping lack of motivation. During times like these it is actually more important to live our lives deliberately, rather than drifting on the tide of current events and daily news.

I notice that the times when I am most motivated is when I have a strong incentive such as practising for a performance, learning a new piece to teach to a student, or going to the gym in the build up to a summer holiday. A strong incentive takes away the element of choice in what we should be doing: if a lion is chasing you, you won’t debate whether to run or watch Netflix – you’ll just run!

Maybe the key to motivation is to unleash the lions upon ourselves: book ourselves into an open-mic slot even though we don’t feel ready; join a band even though we aren’t “perfect” yet. I have been procrastinating starting a YouTube channel as I don’t feel confident enough or “authoritative” enough. But I also realise that confidence will emerge once I begin: action creates confidence.

How could you unleash your lions?